Proportion and Perfection: Ancient Greek Aesthetics and Life Drawing

To the Ancient Greeks, beauty was was structural. It lay in proportion, balance, and harmony. The Greeks sought to understand beauty through sight, reason and geometry. Their aesthetic ideals weren’t divorced from ethics or politics; rather, beauty was a manifestation of order, clarity, and virtue. As Plato expressed, the contemplation of beauty was a path to the divine, an upward ascent from physical form to philosophical truth.

Plato’s Philosophy on Beauty

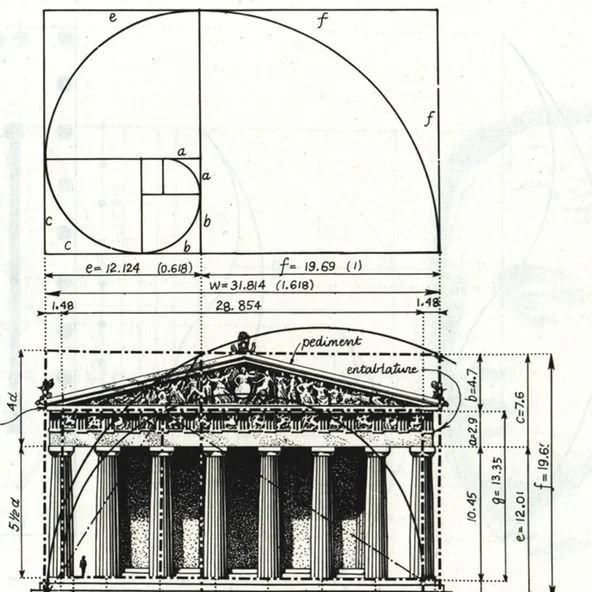

At the heart of Greek visual harmony lies the golden ratio, approximately 1.618, represented by the Greek letter phi (φ)- the inspiration of Santo-FI. This proportion, found throughout nature from seashells to sunflower spirals. Phi was a universal constant to the Greeks, a mathematical embodiment of beauty.

This ratio influenced architectural feats such as the Parthenon, as well as sculptural masterpieces where the human body was rendered in ideal proportions. Ancient Greek thinkers understood mathematical ratios both as measurements and as metaphysical principles governing natural and artistic beauty. In this view, aesthetics and mathematics weren’t separate disciplines - they were two ways of approaching truth.

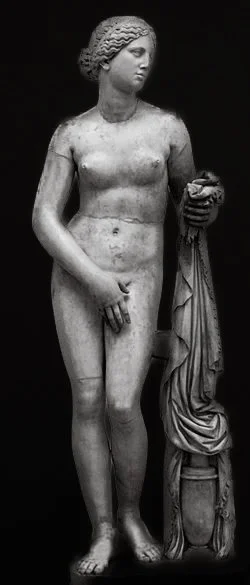

By the fifth century BCE, Greek sculpture achieved a breathtaking quantum jump in realism and anatomical mastery that was unprecedented up until that point - setting a new standard in the representation of the human form. This transformation was not merely technical — it reflected a human-centered worldview in which physical perfection mirrored intellectual and moral virtue.

Aphrodite of Knidos by Praxiteles

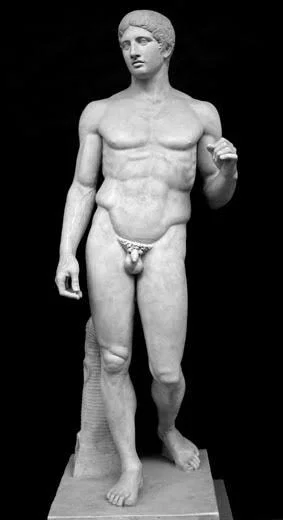

Athletics similarly celebrated the body as a vessel of symmetry and control, reinforcing ideals of societal harmony. Greek sculpture and athletics revered the human body. This idealization of the body was directly linked to the concept of areté (excellence). Statues such as Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer) were based on calculated ratios, crafting a body, which was physically impressive, spiritually and morally elevated.

Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer)

The gymnasium was both a training ground and a philosophical arena. Athletes were shaped for physical contest and for public life. The athletic male nude embodied the values of strength, rational control, and civic duty… the body became a metaphor for the ideal state: proportioned, ordered, and harmonious.

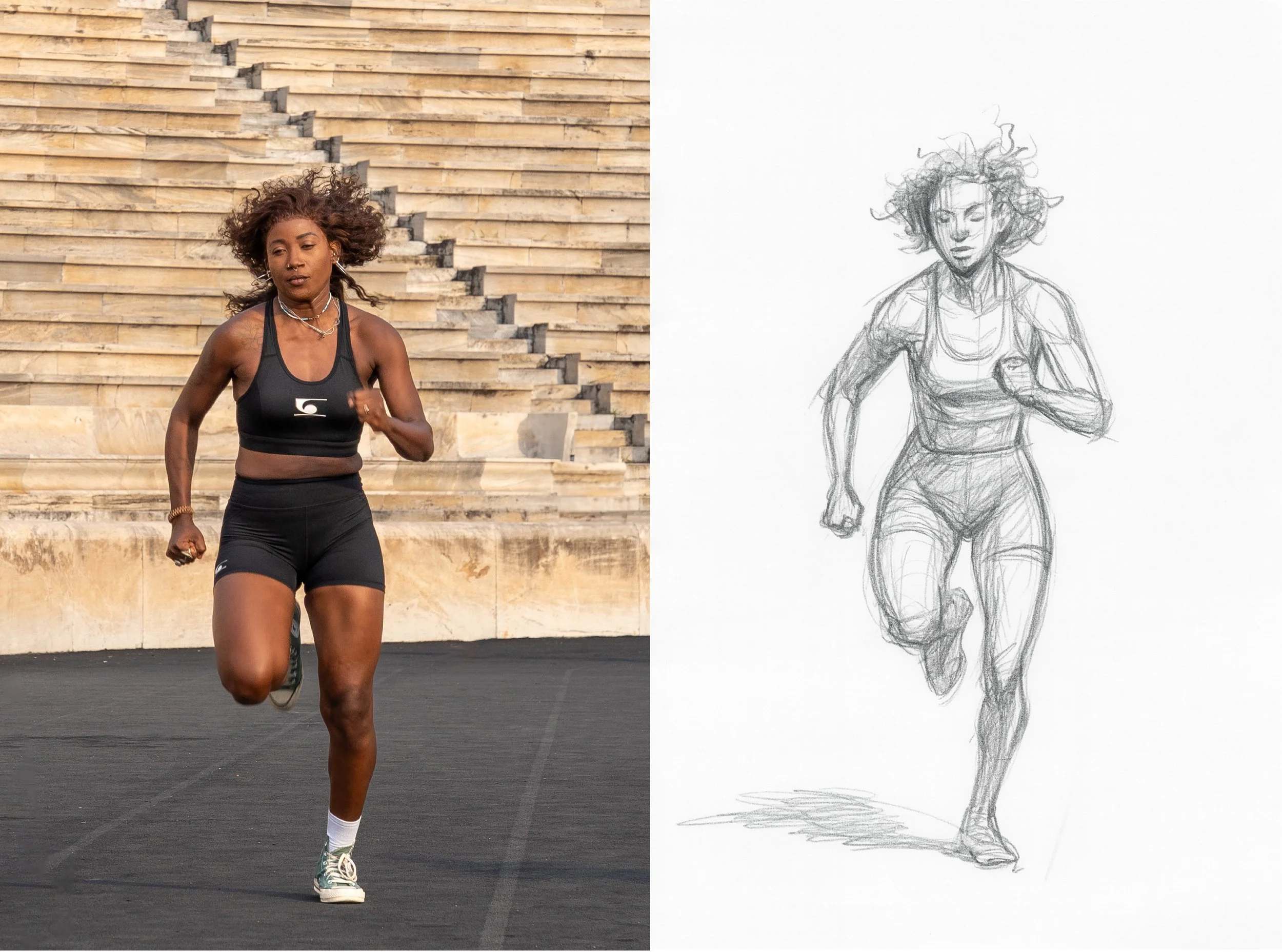

Life drawing today owes much to these classical ideals. When artists observe and render the human body, they continue a lineage that began with Greek sculptors striving to express universal harmony. In art academies around the world, the study of the nude form still emphasizes proportion, gesture, and anatomy—principles rooted in Greek aesthetics.

Far from being a purely technical exercise, life drawing reflects the same philosophical inquiries posed by the Greeks: What makes a body beautiful? How does form relate to function, movement, and meaning? What is the role of idealization versus observation?