Might = Right? Origins of Realpolitik

“The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.”

— Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

“The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.”

— Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

If Plato asked how we should live, Thucydides asked how we actually do. And in that shift, from idealism to realism: political science was born.

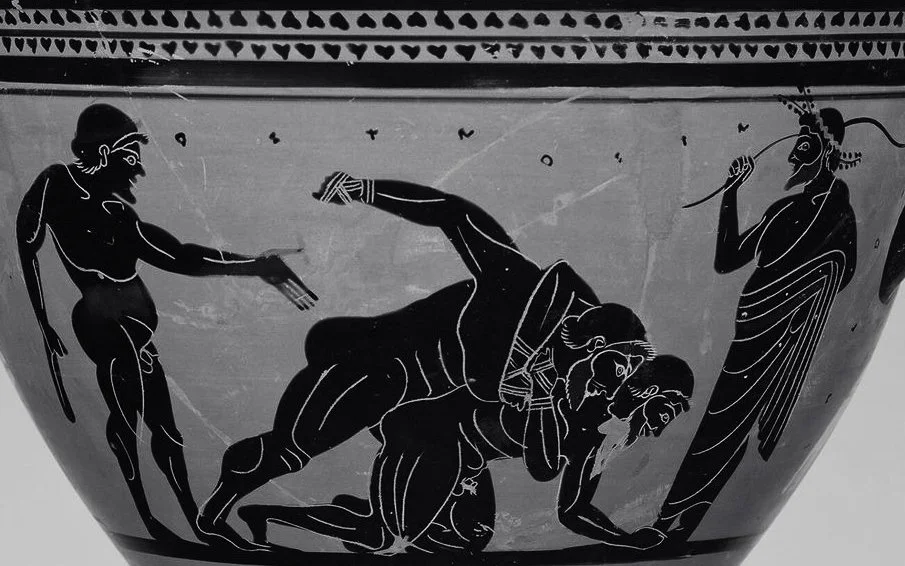

Thucydides didn’t write myths or moral tales. He wrote history. Specifically, the story of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, two great powers locked in a brutal, 27-year struggle for dominance. But what makes his work foundational is in the lens just as much as the details. He wasn’t explaining events through the will of the gods. He was showing how fear, self-interest, and raw power shape human affairs. This was politics, stripped of illusion.

Thucydides was the first to observe international conflict not as a matter of virtue or vice, but as a contest of interest. The Athenian leaders in his account don’t claim moral superiority. They assert that might makes right. Nowhere is this clearer than in the Melian Dialogue, where Athens confronts the neutral island of Melos. The Melians plead for justice. The Athenians respond bluntly: justice only exists between equals in power. Between unequals, the strong rule and the weak endure.

Thucydides was laying the groundwork for what we now call political realism—the idea that states act primarily in pursuit of their own survival, power, and advantage. Idealism, morality, diplomacy — all of these are tools, but none outweigh the hard logic of power.

Fast forward 2,400 years, and the patterns haven’t changed. Political scientists still reference Thucydides to explain major geopolitical tensions; especially one in particular: the rise of China and the response of the United States.

In 2017, Harvard political scientist Graham Allison coined the term “Thucydides Trap” to describe the recurring danger when a rising power threatens to displace an existing one. Just as Athens rose and unsettled the established dominance of Sparta - triggering a catastrophic war — China’s economic and military expansion has sparked anxiety in the U.S. led global order.

Whether it’s trade wars, military exercises in the South China Sea, or competition over AI and semiconductors, the logic remains: when one power grows rapidly, the dominant power feels threatened. That threat, whether rational or not, can turn competitive tension into open conflict.

This is the essence of Thucydidean insight. It’s not about what leaders say. It’s about what they fear. The real causes of war, Thucydides wrote, are “fear, honor, and interest.” Strip away the speeches, and those three drivers still define the headlines.

This isn’t just about great powers either. You see it in smaller conflicts, too. Wherever might determines terms. Where diplomacy is a performance, and the real negotiation happens through leverage. Where alliances shift not out of loyalty, but out of shared threat. It’s in Ukraine. It’s in Taiwan. It’s in the scramble for influence across Africa and the Arctic.

But Thucydides wasn’t only offering a theory of war. He was offering a way of seeing. A way of studying politics that was grounded in evidence, not ideals. He paid attention to speeches, troop movements, alliances, strategies. He analyzed how ambition and fear ripple through decisions. He showed how history could be a method.

In that sense, The History of the Peloponnesian War isn’t just a chronicle of the past. It’s a blueprint for how to think politically. It’s the reason some argue political science does not begin with Plato’s vision of a perfect republic, but with Thucydides’ cold, clear-eyed look at how power actually works.

So much of modern political thought has roots in this. The idea of balance of power, the study of realpolitik, the warnings about entangling alliances; all trace back to this Athenian general turned historian, writing in exile, trying to make sense of a war his city could not win.

And maybe that’s the deeper lesson.

Despite Thucydides’ cold, clear-eyed look at how power actually works, he also tells the story of a civilization that collapsed under the weight of that thinking. Athens, brilliant and ambitious, came to believe too much in its own might. It pursued dominance at the cost of stability, expansion at the cost of restraint. The logic of power, when left unchecked leads not to glory, but ruin. The end of the Peloponnesian Wars was the beginning of the end of Ancient Greece’s Golden Age.

In other words, realism may explain why states act the way they do. But history shows what happens when that mindset becomes a blueprint instead of a warning. Acting out of fear, honor, and interest might be natural. But it’s also the path so many powers have taken just before they fall.

We still live in a world shaped by fear and force. But if we can understand the dynamics…. see them clearly…. we’re not doomed to repeat them blindly.

Power still matters.

But so does perspective.

Proportion and Perfection: Ancient Greek Aesthetics and Life Drawing

Beauty in Ancient Greece was understood as a harmonious balance of form, proportion, and purpose. It was an aesthetic ideal rooted in both mathematics and philosophy.

To the Ancient Greeks, beauty was was structural. It lay in proportion, balance, and harmony. The Greeks sought to understand beauty through sight, reason and geometry. Their aesthetic ideals weren’t divorced from ethics or politics; rather, beauty was a manifestation of order, clarity, and virtue. As Plato expressed, the contemplation of beauty was a path to the divine, an upward ascent from physical form to philosophical truth.

Plato’s Philosophy on Beauty

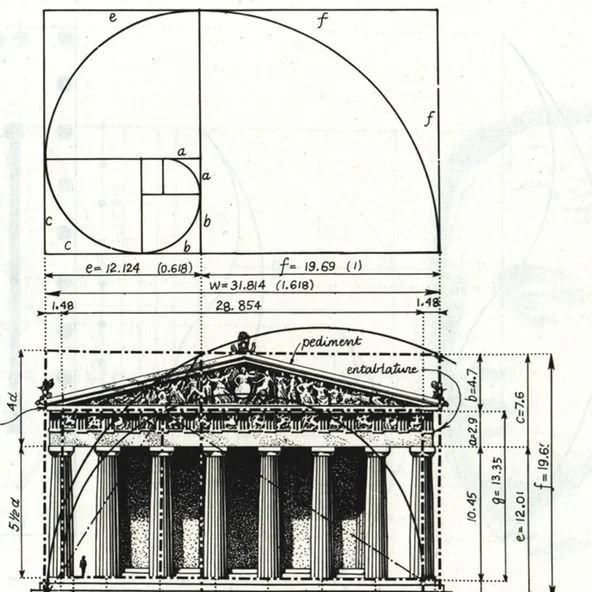

At the heart of Greek visual harmony lies the golden ratio, approximately 1.618, represented by the Greek letter phi (φ)- the inspiration of Santo-FI. This proportion, found throughout nature from seashells to sunflower spirals. Phi was a universal constant to the Greeks, a mathematical embodiment of beauty.

This ratio influenced architectural feats such as the Parthenon, as well as sculptural masterpieces where the human body was rendered in ideal proportions. Ancient Greek thinkers understood mathematical ratios both as measurements and as metaphysical principles governing natural and artistic beauty. In this view, aesthetics and mathematics weren’t separate disciplines - they were two ways of approaching truth.

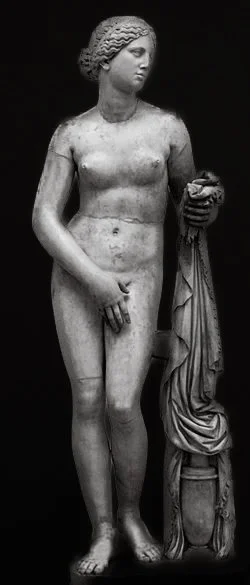

By the fifth century BCE, Greek sculpture achieved a breathtaking quantum jump in realism and anatomical mastery that was unprecedented up until that point - setting a new standard in the representation of the human form. This transformation was not merely technical — it reflected a human-centered worldview in which physical perfection mirrored intellectual and moral virtue.

Aphrodite of Knidos by Praxiteles

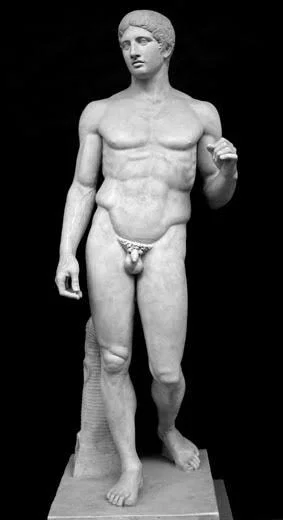

Athletics similarly celebrated the body as a vessel of symmetry and control, reinforcing ideals of societal harmony. Greek sculpture and athletics revered the human body. This idealization of the body was directly linked to the concept of areté (excellence). Statues such as Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer) were based on calculated ratios, crafting a body, which was physically impressive, spiritually and morally elevated.

Polykleitos’ Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer)

The gymnasium was both a training ground and a philosophical arena. Athletes were shaped for physical contest and for public life. The athletic male nude embodied the values of strength, rational control, and civic duty… the body became a metaphor for the ideal state: proportioned, ordered, and harmonious.

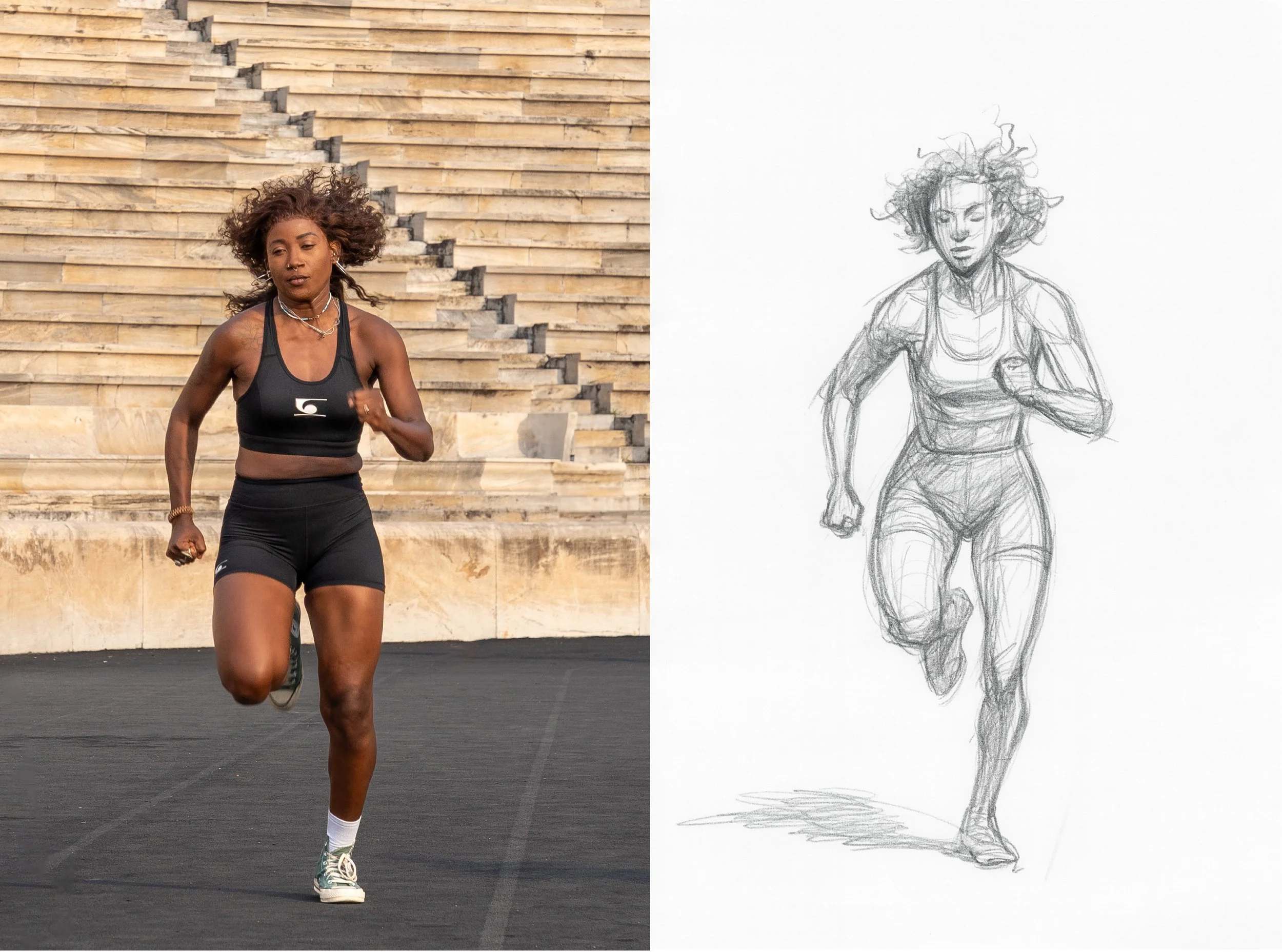

Life drawing today owes much to these classical ideals. When artists observe and render the human body, they continue a lineage that began with Greek sculptors striving to express universal harmony. In art academies around the world, the study of the nude form still emphasizes proportion, gesture, and anatomy—principles rooted in Greek aesthetics.

Far from being a purely technical exercise, life drawing reflects the same philosophical inquiries posed by the Greeks: What makes a body beautiful? How does form relate to function, movement, and meaning? What is the role of idealization versus observation?

The Odyssey of the Irrationally Rational

“It is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified.”

— Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

“It is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified.”

— Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

To be human is to live in tension.

Friedrich Nietzsche saw that clearly in The Birth of Tragedy, where he explored how Greek tragedy wasn’t just a form of entertainment—it was a mirror. A reflection of the struggle between two opposing forces at the core of life itself: the Apollonian and the Dionysian.

Apollo stood for clarity, reason, harmony, and control.

Dionysus embodied chaos, instinct, passion, and surrender.

Greek tragedy, according to Nietzsche, worked because it didn’t try to resolve these forces. It held them together. It let them clash. In that clash was beauty. In that beauty—truth.

The Greeks didn’t flinch from contradiction. They built myths and temples, yes—but they also honored madness and ecstasy through ritual. They debated politics in the agora and danced in Dionysian frenzy at night. Their genius wasn’t in picking sides—it was in holding the paradox.

That’s why tragedy mattered. It wasn’t just about a hero falling. It was about a hero trying—desperately—to hold order in a world ruled by forces beyond his control. Oedipus seeks truth and destroys himself with it. Pentheus fights chaos and gets torn apart by it. Neither wins. But in the attempt, something is revealed.

That’s the point.

The Greeks called it arete—excellence. Not just skill, but the pursuit of becoming your fullest, most complete self. It applied to warriors, poets, athletes, and citizens alike. Arete was effort. It was character. It was a lifelong attempt to live well.

But even as they pursued excellence, the Greeks didn’t pretend the path was clean. They knew that within every rational aim lurked irrational drives. Every push toward perfection was shadowed by chaos, temptation, loss. That was life. That was the tragedy.

And Nietzsche knew it too. His writing wasn’t a call to give in to disorder, but to acknowledge its presence. To see the wildness and work with it—not against it.

In a world obsessed with control—optimization, metrics, systems—the Apollonian has won the culture war. We praise what we can measure. We reward order. We idolize the person with the plan.

But beneath the surface, Dionysus waits.

The burnout. The breakdown. The burst of inspiration. The sudden loss. The gut feeling you can’t explain. The need to dance, cry, break something, quit something, create something. That’s Dionysus knocking.

To strive for arete today is not to silence that voice—but to include it. To make space for the irrational, the unpredictable, the ecstatic. Because without it, the picture is incomplete. And worse—it becomes brittle. It cracks.

Greek tragedy never gave us heroes who won cleanly. It gave us heroes who tried—who stepped into the chaos, who acted, who fell, and in falling revealed something true.

That’s still the task. To strive for excellence. To structure our lives with intention. But also to let in the wild. To accept that we are not fully in control. That we’re shaped not only by plans, but by what resists them.

To live well is to hold that tension.

To strive with discipline and act with instinct.

To lead with reason and move with passion.

To stay irrationally rational.

The Drip and the pursuit of Kleos

“I too shall lie in the dust when I am dead,” Achilles says. “But now let me win noble renown.”

— The Iliad

“I too shall lie in the dust when I am dead,” Achilles says. “But now let me win noble renown.”

— The Iliad

Kleos—glory—was the highest value in Ancient Greek culture. It wasn’t abstract. It wasn’t about personal enlightenment or quiet virtue. It was about being remembered. Being talked about. Being known. A name that echoed after death.

You see it throughout Homer’s Iliad. Achilles chases kleos through unmatched skill in battle. Agamemnon seeks it through command and authority. Even Helen, at the center of the war, becomes immortal not through action, but through beauty—her name inscribed in legend.

The Greek worldview was deeply human-centered. Gods had human shapes, flaws, rivalries. Glory wasn’t a gift from heaven—it was earned through contest (agon) and excellence (arete). And this excellence wasn’t just a private virtue. It had to be witnessed. Memorialized. That’s kleos.

This wasn’t just personal ambition. In a world where even the best souls faded into shades in Hades, where there was no heavenly reward for righteousness, kleos offered a kind of immortality. If your body would vanish, your name didn’t have to. People would know what you did. They would tell the story.

So the Greeks built their culture around competition. Athletics, warfare, politics, art—every domain became a stage for excellence. They even made artistic commissions and political roles into contests. The very word agon, which gives us “agony,” came from this mindset of struggle toward greatness.

And what did kleos look like? Materially, it was armor, horses, robes, epic poems. Tangible tokens of accomplishment. Homeric warriors fought over spoils not just for wealth—but because those items meant something. They proved you’d done something worth remembering.

Sound familiar?

Kleos may sound ancient, but the chase hasn’t changed. Today, we flex with different gear—shoes, watches, cars, stories we post, images we curate. It’s not the battlefield of Troy. It’s the arena of visibility. What we wear, collect, or share signals something about who we are—or who we want to be seen as.

You see it clearly in the world of collectibles. A holographic Charizard isn’t just a trading card—it’s status, story, nostalgia. It’s a symbol that says: “I knew. I played. I valued this before it was valuable.” Or sometimes: “I can afford to own what others can’t.” In either case, it’s legacy through possession.

The rarest cards sell for hundreds of thousands, not just because of condition or rarity, but because of the cultural memory tied to them. They become modern heirlooms—proof that someone reached the top of a certain kind of mountain, whether through mastery, money, or timing. They’re kleos, slabbed in acrylic.

Think beyond cards. Think of luxury brands. Championship rings. Signed memorabilia. Concert posters. Even social media timelines. What’s being constructed isn’t just a record—it’s a persona. An echo. Our own digital or physical version of immortality. We want to be remembered, or at least recognized, for something.

The Greeks didn’t see the pursuit of kleos as ego-driven vanity. It was a way of striving toward excellence. Of becoming more than ordinary. In Homer’s world, glory wasn’t guaranteed—but it was worth pursuing.

Still, the competitive ethic wasn’t without its dangers. The Greeks’ obsession with glory often led to conflict. When politics failed, they turned to war. Their city-states, each proud of its legacy, tore themselves apart. Kleos was a double-edged sword: it inspired greatness, but also division and destruction.

That tension remains today. The pursuit of status, recognition, and legacy can push us to achieve, to innovate, to stand out. But it can also lead to burnout, comparison, consumerism, and hollow ambition. When kleos becomes the only goal, we risk building a life that’s seen—but not felt.

In Ancient Greece, the symbols of glory were inseparable from the effort behind them. If we’re going to chase glory today—through what we own, collect, create, or share—maybe we should ask: does it point to something real? Something excellent? Something worth remembering?

Because while the gear has changed, the impulse hasn’t. To be seen. To stand out. To leave a mark.

That’s kleos. Ancient—and still alive.

Importance of Friendship

"For without friends no one would choose to live, though they had all other goods."

— Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

"For without friends no one would choose to live, though they had all other goods."

— Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

We’re more connected than ever—group chats, playlists, tagged stories. And yet, loneliness lingers.

Aristotle saw this coming. In Nicomachean Ethics, he stated that even with all the riches in the world, no one would choose to live without friends.

He laid out three kinds of friendship: pleasure, utility, and virtue.

Friendships of pleasure are built around shared joy—surfing at sunrise, being in a flow state while rolling, solving a bouldering problem together. They’re light, energizing, often fleeting.

Friendships of utility are about mutual benefit. A training partner prepping you for comp. A last-minute belayer for an outdoor climb. These relationships are helpful, practical—and sometimes transactional.

Django Unchained - Dr. Schultz (left) and Django (right); Dr. Schultz helps Django find his wife, inexchange Django helps Dr. Schultz find bounties.

But the rarest, and most powerful, is the friendship of virtue. The kind where two people challenge each other to grow. Where you're seen—not just for who you are, but for who you could become.

Jujutsu Kaisen - Itadori (left) Todo (right); Itadori and Todo sincerely care for one another while at the same time they push one another to become not only better sorcerers but also better people.

These friends hold you accountable, lift you up, and walk with you toward something better.

That tension cuts deep: we have endless ways to stay in touch—and still, real connection slips away. That’s why real friendship—the kind that Aristotle believed was the foundation of a good life—matters now more than ever.

In Ancient Greece, the gymnasion wasn’t just a training ground. It was where people came to debate, move, learn, and grow together.

We like to think our gatherings carry that same spirit. Surfboards, mats, crash pads—modern pillars for the same kind of connection. But the impulse is the same.

To show up.

To be seen.

To belong.

To become more than you were when you arrived.

At SANTO-FI, we honor all three friendships. Because every kind of friend has a place. Our gatherings aren’t about status or competition. They’re about building the kind of community where any of these friendships can take root—and maybe, if you’re lucky, you’ll find that rare one.

SANTO-FI Top Roping Gathering - 06Apr2025