The Drip and the pursuit of Kleos

“I too shall lie in the dust when I am dead,” Achilles says. “But now let me win noble renown.”

— The Iliad

Kleos—glory—was the highest value in Ancient Greek culture. It wasn’t abstract. It wasn’t about personal enlightenment or quiet virtue. It was about being remembered. Being talked about. Being known. A name that echoed after death.

You see it throughout Homer’s Iliad. Achilles chases kleos through unmatched skill in battle. Agamemnon seeks it through command and authority. Even Helen, at the center of the war, becomes immortal not through action, but through beauty—her name inscribed in legend.

The Greek worldview was deeply human-centered. Gods had human shapes, flaws, rivalries. Glory wasn’t a gift from heaven—it was earned through contest (agon) and excellence (arete). And this excellence wasn’t just a private virtue. It had to be witnessed. Memorialized. That’s kleos.

This wasn’t just personal ambition. In a world where even the best souls faded into shades in Hades, where there was no heavenly reward for righteousness, kleos offered a kind of immortality. If your body would vanish, your name didn’t have to. People would know what you did. They would tell the story.

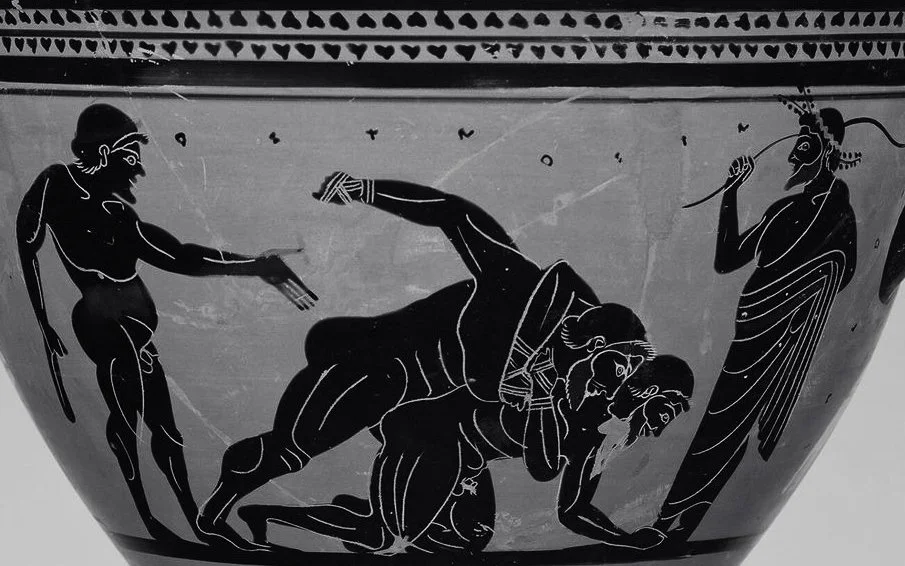

So the Greeks built their culture around competition. Athletics, warfare, politics, art—every domain became a stage for excellence. They even made artistic commissions and political roles into contests. The very word agon, which gives us “agony,” came from this mindset of struggle toward greatness.

And what did kleos look like? Materially, it was armor, horses, robes, epic poems. Tangible tokens of accomplishment. Homeric warriors fought over spoils not just for wealth—but because those items meant something. They proved you’d done something worth remembering.

Sound familiar?

Kleos may sound ancient, but the chase hasn’t changed. Today, we flex with different gear—shoes, watches, cars, stories we post, images we curate. It’s not the battlefield of Troy. It’s the arena of visibility. What we wear, collect, or share signals something about who we are—or who we want to be seen as.

You see it clearly in the world of collectibles. A holographic Charizard isn’t just a trading card—it’s status, story, nostalgia. It’s a symbol that says: “I knew. I played. I valued this before it was valuable.” Or sometimes: “I can afford to own what others can’t.” In either case, it’s legacy through possession.

The rarest cards sell for hundreds of thousands, not just because of condition or rarity, but because of the cultural memory tied to them. They become modern heirlooms—proof that someone reached the top of a certain kind of mountain, whether through mastery, money, or timing. They’re kleos, slabbed in acrylic.

Think beyond cards. Think of luxury brands. Championship rings. Signed memorabilia. Concert posters. Even social media timelines. What’s being constructed isn’t just a record—it’s a persona. An echo. Our own digital or physical version of immortality. We want to be remembered, or at least recognized, for something.

The Greeks didn’t see the pursuit of kleos as ego-driven vanity. It was a way of striving toward excellence. Of becoming more than ordinary. In Homer’s world, glory wasn’t guaranteed—but it was worth pursuing.

Still, the competitive ethic wasn’t without its dangers. The Greeks’ obsession with glory often led to conflict. When politics failed, they turned to war. Their city-states, each proud of its legacy, tore themselves apart. Kleos was a double-edged sword: it inspired greatness, but also division and destruction.

That tension remains today. The pursuit of status, recognition, and legacy can push us to achieve, to innovate, to stand out. But it can also lead to burnout, comparison, consumerism, and hollow ambition. When kleos becomes the only goal, we risk building a life that’s seen—but not felt.

In Ancient Greece, the symbols of glory were inseparable from the effort behind them. If we’re going to chase glory today—through what we own, collect, create, or share—maybe we should ask: does it point to something real? Something excellent? Something worth remembering?

Because while the gear has changed, the impulse hasn’t. To be seen. To stand out. To leave a mark.

That’s kleos. Ancient—and still alive.